OVerview

The “AI doctor” isn’t a future concept. It’s already here, hiding in plain sight: millions of patients are using LLMs as de facto clinicians, holding health-related conversations and making informed decisions before a human ever enters the loop.

This piece is a field guide for investors, founders, and healthcare leaders who want a clear-eyed view of what’s happening and what actually matters next. Our core intent is simple: reorient the conversation from AI doctors as a hypothetical to discussing the autonomy creep that’s already underway, and map the real bottlenecks that will decide outcomes in this market.

Here’s the framework:

Define the AI doctor: not “clinical AI,” not decision support, but a system that can make end-to-end medical decisions for patients without real-time human sign-off, and where oversight becomes optional rather than structural. We then map the autonomy ladder from administrative tools to true decision-makers, drawing lessons from the more mature evolution of AI in software.

Assess the readiness of current AI models and the “good enough” threshold they've already crossed: Recent benchmarks demonstrate that frontier models now match or exceed physician performance on core reasoning tasks. There are places in medicine where the cognitive bottleneck has been solved. The remaining barriers are execution, integration, trust, and where models still break (especially under uncertainty and clinical judgement, rather than reasoning).

Follow the demand physics: why “AI front doors” are likely to be net utilization creators (Jevons-style). Making healthcare access easier appears to increase total consumption rather than reduce it. In a system already facing a projected shortfall of 86,000 physicians by 2036, this dynamic has profound implications for where AI autonomy becomes not just valuable but structurally necessary.

Name the real endgame and the real winners: Model quality will converge, and advantage will accrue to whoever owns the rails that make autonomy executable and governable, namely distribution, context access, EHR-grade actuation, safety instrumentation, and the sensor-to-decision stack, all while navigating the gating constraints (liability, payment rails, bias).

The question isn’t “can a model reason like a doctor?” In more and more characterized settings, the answer is yes. The real question is who can build the rails that turn that reasoning into accountable, closed-loop care inside the messy reality of healthcare systems.

Section 1: Defining the “AI Doctor”

1a. What does the term actually mean?

What exactly is an “AI doctor”? The term is both overused and underdefined. It’s been stretched to cover everything from generalized chat models like ChatGPT to prediction engines that estimate risks such as mortality or hospital length of stay [Source: NYU]. It has also been used to describe more ambitious efforts to build virtual specialists that know which labs, imaging, medications, and referrals to order for any patient in any health system [Source: Ethan Goh, Stanford].

So what actually counts? Is an AI doctor defined by diagnostic reasoning? The ability to prescribe autonomously? Perform an exam? Express empathy? Or is it simply the legal entity responsible for the advice you receive?

We’ll use a functional definition: an AI doctor is an AI system that can make end-to-end medical decisions for patients without needing real-time human sign-off. Human oversight becomes optional; the clinician shifts from operator to supervisor. This is a crucial distinction: the true AI doctor is not decision-support; it’s a decision-maker.

By that definition, the AI doctor isn’t hypothetical. It’s already emerging in the wild.

While academic and regulatory circles are busy drafting frameworks, taxonomies, and guardrails for “patient-facing AI,” consumers are routing around them. LLMs like ChatGPT are fielding health questions from millions of people today.

Roughly one in six Americans already asks an LLM for health advice on a regular basis [Source: NYT/KFF]. People are even uploading full medical records into these LLMs despite every warning label to the contrary [Source: NYT].

This is the natural evolution of “Dr. Google,” but it’s fundamentally different. Search gives you pages of vague, sometimes contradictory links and forces you to DIY a plan. A modern conversational AI system gives you something that feels like a clinician on demand. It is conversational, friendly, direct, and confident in the next step.

A recent NYT essay captures the shift. A patient took a longevity supplement after social media hype, obtained it through a direct-to-consumer telehealth flow, then asked ChatGPT about his symptoms. The model flagged a possible blood clot, prompting him to go to the ER, where the physician put it bluntly: “A.I. diagnosed his blood clot — I only confirmed it.” That is the difference in one story. Search gives you information. LLMs increasingly deliver a working diagnosis and trigger action [Source: NYT].

Patients are behaving as if they’re talking to a doctor, regardless of the fine print. In one study, up to 81% of U.S. adults reported finding LLM-based advice more useful than their own doctor’s [Source: PubMed].

1b. Driving forces behind AI doctors

The demand drivers are straightforward:

Severe supply–demand mismatch. The AAMC projects a physician shortfall of up to ~86,000 by 2036, with primary care as the main pinch point [Source: AAMC]. That translates into difficulty getting an appointment at all, an average wait time of a month if you do [Source: Forbes], and rushed encounters when you finally do. The median primary care visit lasts ~18.9 minutes [Source: JAMA], covering about six topics [Source: PubMed], with only about five minutes of attention spent on the main issue.

Poor user experience. Even if you imagine a world with enough clinicians, getting care still feels incredibly broken. Patients today are juggling portals and phone trees, waiting weeks for an appointment slot, showing up early to fill out physical paperwork, waiting again for a doctor who is running behind, and walking out with no price transparency or clear next steps. At every turn, the system feels slow, fragmented, and oddly manual (where else are we still filling out paper forms?).

This is made even more jarring by the baseline expectations that today’s patients carry from the rest of modern consumer life: one-click checkout, fast shipping, real-time updates, all wrapped in polished, intuitive UX. The contrast is so stark that healthcare can feel like it is operating on an entirely different set of expectations, and patients feel that gap every time they try to access care.

Financial pain and price opacity. Care in the U.S. is expensive, unpredictable, and increasingly out-of-pocket [Source: KFF]. High-deductible plans, surprise bills, and opaque pricing make touchpoints feel unpredictable and often uncomfortable. By contrast, an “AI doctor” feels like a zero-marginal-cost consult that is instant, always-on, no co-pay, no explanation of benefits (EOB) three weeks later. For a huge swath of patients, the real choice isn’t “AI vs top-tier physician,” it’s “AI vs nothing or an expensive, risky interaction with the system.” That economic anxiety makes free (or near-free) AI guidance incredibly attractive and turns AI doctors into the rational first (and sometimes only) stop.

Layer on top of this a generation of digital natives who have been self-diagnosing online for years. For them, “AI doctor” isn’t a foreign concept; it’s a more convenient and personalized version of behavior they already exhibit.

The result is torrential pull toward AI doctors. With no policy change, no new CPT codes, and no formal licenses, patients are voting with their clicks. Wherever there is that kind of demand, entrepreneurs will follow. Founders will build things people want. Here, the answer is blunt: people want AI doctors.

1c. The value to be captured on the way to AI doctors

There are no fully functional, regulatory-approved “AI doctors” yet, but companies are already commercializing intermediate tiers of the autonomy ladder.

To understand how this progression unfolds and where value is captured, it helps to look at a domain where AI autonomy is already more mature: software engineering. In that world, AI has advanced from lightweight adjuncts to semi-autonomous agents, creating new business models at each step.

2018–2020. Step I: Administrative AI (Autocomplete 1.0). Tools such as Codota, Tabnine, Kite, and early IntelliSense-style IDE autocomplete brought machine learning into the editor to predict the next token or line of code. These systems handled boilerplate well, such as imports, syntax completion, and repetitive patterns, but lacked semantic understanding and any awareness of broader system behavior. They were unmistakably administrative assistants, yet they proved a critical point: developers were willing to accept and ship machine-generated code so long as it remained confined to low-risk, non-decision-owning tasks.

2021–2023. Step II: Assistive AI (LLM Pair Programmers). Large language models upgraded autocomplete into true pair programming. Tools like GitHub Copilot, Replit Ghostwriter, Codeium, Amazon CodeWhisperer, and Gemini Code Assist could generate full functions, files, docstrings, and tests, as well as explain unfamiliar code and APIs in natural language. GitHub reported developers completing tasks ~55% faster, with AI contributing a substantial fraction of code in enabled files [Source: Microsoft]; Copilot surpassed 1 million paid seats across tens of thousands of companies, with “almost half” of user code AI-generated [Source: AI News]. In parallel, Stack Overflow usage declined by roughly 50–70% from pre-LLM peaks as “ask the AI first” replaced traditional search [Source: DevClass]. Despite this leap, humans still initiated tasks, selected outputs, and retained full responsibility for what shipped.

2023–present. Step III: Supervised Autonomous AI (AI Executing Under Review). The next transition shifted AI from suggestion to execution under supervision. Tools such as GitHub Copilot Chat (workspace mode), Sourcegraph Cody, Tabnine Chat (enterprise), and early Cursor workflows enabled AI to interpret tickets, reason over large codebases, generate multi-file diffs, run tests, and propose fixes, but all of these motions were subject to human review before merge. Developers no longer edited every line themselves; instead, they supervised AI execution. Value creation moved beyond faster coding toward offloading entire, well-scoped units of work to machines operating within defined guardrails.

Emerging. Step IV: Autonomous AI Engineers (AI Running the Loop). The most advanced systems now function as autonomous software agents. Products such as Cursor (agent mode), Devin, Windsurf, Antigravity, and similar “AI engineer” tools accept high-level goals or tickets, draft implementation plans, modify multiple files, run commands and tests, and iterate until tasks pass with minimal real-time human involvement. Humans primarily review diffs, handle edge cases, and manage deployment risk. At scale, companies like Robinhood report that roughly 50% of new code is written by AI, with near-universal internal adoption [Source: BI]. Replit and Lovable push autonomy even further, enabling non-coders to create production-grade apps using only natural language, with the AI handling architecture, implementation, and iteration. The defining shift is autonomy: the AI owns the execution loop rather than advising within it.

The key takeaway for healthcare is that meaningful value was captured at every rung of the autonomy ladder, and long before anything resembled a fully autonomous “AI engineer.” Productivity gains, workflow lock-in, and new pricing power all emerged incrementally as AI systems moved from narrow assistance to broader ownership of work. Medicine is following the same trajectory. The AI doctor will not arrive as a single regulatory event, but through a sequence of autonomy upgrades: from systems that automate clerical tasks, to systems that reason about clinical decisions, to systems that act within the encounter, and ultimately to systems that own the clinical loop with optional human oversight.

Stage 1: Administrative. AI at this stage automates administrative work that directly burdens clinicians but sits entirely outside clinical judgment or medical decision-making. This is the most mature and widely deployed layer of healthcare AI today. The clearest examples are ambient AI scribes such as Nuance DAX, Abridge, Ambience, Knowtex, and DeepScribe, which convert clinician–patient conversations into structured notes, orders, and documentation artifacts that physicians would otherwise produce manually. These systems reduce cognitive load, documentation time, and burnout, but they do not interpret findings, make diagnoses, or recommend treatment. Also within this stage are revenue-cycle and utilization workflows that clinicians are routinely pulled into, including prior authorization, documentation for medical necessity, and payer communications. Platforms such as AKASA and Infinitus automate these processes by handling data extraction, form completion, and insurer interaction, reducing the time clinicians spend justifying care they have already decided to provide. These systems reduce administrative burden and physician task burden but do not diagnose, treat, triage, or prescribe, and they do not assume any clinical responsibility.

Stage 2: Assistive. AI at this stage participates in early clinical decision-making, including symptom intake, preliminary triage, and care navigation, but cannot independently diagnose, treat, or prescribe. These systems primarily function as AI-powered front doors, engaging patients directly and advancing decision-making up to a clear boundary that requires physician review or sign-off. Examples include Doctronic and Counsel Health, which collect histories, reason through symptoms, suggest next steps, and route patients to appropriate care. While they may generate provisional assessments or care pathways, clinical authority and responsibility remain with licensed clinicians.

By this definition, general-purpose LLMs such as ChatGPT also belong in Stage 2: they are explicitly non-authoritative by design, yet already perform the core cognitive functions of early medical decision-making, including symptom interpretation, differential diagnosis, and care navigation.

Also within this stage are clinician-facing assistive tools such as OpenEvidence for differential brainstorming, guideline interpretation, and documentation. These tools augment clinician cognition but are non-authoritative and carry no clinical autonomy.

Stage 3: Supervised Autonomous (Task-Specific, Context-Bounded). AI at this stage can autonomously diagnose, triage, treat, and or prescribe within a narrowly defined clinical task or domain. These systems are fully autonomous at the task level, but they remain context-bounded, meaning they cannot reliably incorporate the patient’s full clinical picture such as longitudinal history, physical exam findings, comorbidities, competing diagnoses, or evolving clinical context. As a result, clinician oversight is still required, not only for regulatory or liability reasons, but because human judgment is necessary to integrate broader context and assume responsibility for the overall medical decision. In practice, this includes highly constrained precedents such as closed-loop insulin dosing systems, protocolized medication titration in chronic disease or ICU settings, and FDA-cleared diagnostic tools in radiology and pathology. For example, imaging-based stroke triage systems may autonomously detect suspected large vessel occlusion and trigger downstream workflows, but a physician must still evaluate the patient end to end to confirm the diagnosis, assess for false positives, and determine treatment and disposition.

Stage 4: Autonomous (Context-Complete). AI at this stage would function as a generalizable, fully autonomous clinical actor, capable of diagnosing, triaging, treating, and prescribing without real-time human supervision. The defining feature of this stage is not simply the absence of oversight, but the ability to reason over the full clinical context of the patient, including longitudinal medical history, medications, labs, imaging, prior clinician notes, constraints, and evolving clinical trajectories, and to integrate that context into safe, end-to-end medical decision-making. Because these systems would be task-agnostic and context-complete, human review would no longer be structurally required to compensate for missing information or limited scope. No such systems exist today, and the road ahead is challenging: simply adding more context is not always a win, since larger context windows can introduce noise and distract from the signal that actually matters. While research prototypes and internal pilots have demonstrated strong performance in simulations and narrow scenarios, deployment of fully autonomous clinical systems remains constrained by safety, trust, liability, governance, and regulation.

The march toward AI doctors is most notably happening through two complementary paths that both currently live, at least in practice, inside Stage 2: Assistive AI. On the consumer-facing side, front-door systems like Counsel Health and Doctronic increasingly perform the core cognitive work of medicine while remaining formally non-authoritative. Counsel markets itself as an “MD + AI front door,” blending physician oversight with AI-driven reasoning to resolve the majority of patient issues: “As clinicians validate and reinforce the AI recommendations, Counsel steadily makes more of its interactions autonomous. Like driverless cars, the shift from copilot to autopilot will happen slowly, then all at once” [Source: Andreessen Horowitz]. Doctronic goes further, openly embracing the “AI doctor” label and producing the same structured outputs a clinician would: a full SOAP note, differential diagnosis, and a leading diagnosis with recommended next steps. While users must still acknowledge that they will consult a real clinician, the AI is already generating the decision-making artifacts that define clinical practice, with humans retained primarily as what seems like a legal and regulatory backstop [Source: Lightspeed Venture Partners].

In parallel, clinician-facing ambient and workflow AI systems are approaching the same endpoint from the inside of the health system. Tools such as Abridge, Nuance DAX, and Epic’s embedded AI are officially framed as administrative or assistive, yet they increasingly synthesize encounters into assessments and plans, structure problem lists, highlight guideline-relevant information, and pre-populate actions within the electronic health record. These systems remain classified as Stage 2 because clinicians retain final sign-off, but in practice they already control attention, framing, and workflow, which are the precursors to decision ownership. The result is a convergence at Stage 2: consumer AI moving “up” toward clinical authority and enterprise AI moving “down” toward execution. For investors and regulators, the implication is unavoidable. The AI doctor will not arrive as a sudden leap from non-clinical to autonomous care; it will emerge as Stage 2 systems quietly assume more of the reasoning and decision-making loop, until human oversight becomes a formality rather than the foundation of care.

A critical nuance in healthcare is that, unlike software development, Stage 2 systems are already being used by end users as de facto final decision-makers. While assistive medical AI tools are explicitly non-authoritative by design, many patients today treat general-purpose LLMs such as ChatGPT as their “last doctor,” using them to decide whether to seek care, which treatments to pursue, or whether to accept or decline a clinician’s recommendation. This behavior emerges naturally from the combination of conversational fluency, medical knowledge, and accessibility, even in the absence of formal diagnostic or prescribing authority. Importantly, this dynamic is largely unique to healthcare: in software, non-coders could not realistically use Stage 2 tools to independently build or ship production systems, whereas in medicine, lay users can and do act on AI-generated guidance without professional mediation. As a result, healthcare is already experiencing downstream effects of AI autonomy in practice before autonomy exists in regulation, creating a widening gap between how AI is officially classified and how it is actually used in the real world.

1d. The build pipeline: from protocolized to specialties to the physical world

In 1c, we described autonomy as a spectrum: systems that first inform decisions, then assist in decisions, and eventually act with optional human oversight. An equally important dimension is where in medicine that autonomy emerges. Although progress has been happening across many domains in parallel, the center of gravity has tended to move over time. Early efforts concentrated on more protocolized areas such as radiology and pathology. Attention then shifted toward the fuzzy cognitive work of clinical decision support and clinical data management for generalist medicine. Most recently, the field has entered the earliest innings of autonomy in robotics and the physical world.

It is important to emphasize that this shift in focus does not mean development in earlier areas has slowed or stopped. Radiology and pathology continue to see meaningful advances even as the spotlight moves elsewhere. The trajectory is less a sequence of handoffs and more a widening field, with multiple domains advancing simultaneously as the technology matures.

1) Protocolized medicine: rules, images, and narrow labels. This was the industry’s first center of gravity, and it’s also the cleanest bridge to later stages of autonomy. Not because the work is “easy” (radiology and pathology are not), but because the problem geometry is tractable: structured inputs (pixels, waveforms), standardized reading protocols, and well-labeled outcomes. Compared to the fuzzy, longitudinal ambiguity of primary care, this slice of medicine is relatively bounded. That boundedness is exactly what makes task-level autonomy possible.

In practice, that means these tools naturally live in Stage 3+: they can operate autonomously with oversight within a narrow task (flagging a bleed, detecting a large vessel occlusion), but they’re context-limited by design in their simplest form. They don’t own the full patient. They own a discrete decision inside a workflow, and then hand off to a seasoned clinician who incorporates clinical context to finalize the call. That’s supervised autonomy: machine executes; human assumes responsibility for the end-to-end decision.

Because definitions are clear, this is where AI has the deepest regulatory track record. Of the ~1,000 FDA-cleared clinical AI applications, roughly 70% are in radiology [Source: Radiology Business]. Incumbents like Aidoc and Viz.ai have industrialized detection of intracranial hemorrhage and large vessel occlusion [Source: VizAI, Aidoc]. This month, Pranav Rajpurkar’s a2z radiology received clearance for a device that flags seven urgent abdominal findings simultaneously [Source: A2Z radiology]. Over time, as these systems mature, we should expect the context-limited window to grow to refine task-level decisions by sharpening the underlying prior without breaking the autonomy boundary.

2) The fuzzy brain of medicine: context, ambiguity, and longitudinal reasoning. As the field widened, attention shifted to the messy cognitive work that feels like “being a doctor”: synthesizing conflicting histories, balancing co-morbidities, and deciding whether a patient needs a script or just reassurance.

This is the current center of gravity. Companies like Doctronic and Counsel sit explicitly here, moving from narrow detection to broad reasoning. Technically, this type of problem-solving was not solvable at scale until the jump from classifiers to LLM-based agents. With the emergence of tools like ChatEHR and Glass Health, we are seeing the ability to integrate and query entire charts and guidelines [Source: Stanford, Glass Health].

The unit of work has shifted from a transaction (triaging the order of scan review, classifying an image) to an encounter (managing a case). This is where the AI doctor begins to feel real; it’s now conversational, longitudinal, and context-aware. It is the transition from tools that inform to agents that assist and, increasingly, act.

3) The physical frontier: interventions, robots, and world models. The same infrastructure that enables an AI doctor to read a chart, order labs, and prescribe medications must eventually extend into physical space: examining patients, manipulating instruments, and executing procedures. Robotics is simply where the "execution rights" we discussed earlier become tangible. If Stage 4 autonomy means optional human oversight over clinical decisions, then the full expression of that autonomy includes not just cognitive work but physical intervention. While surgery is often assumed to be the last domino to fall, the breach is already visible.

Johns Hopkins’ STAR robot has performed autonomous soft-tissue surgery with a 100% success rate across eight different ex vivo gallbladdersafter training on just 17 hours of footage on, planning and executing its own sutures [Source: JHU]. Maestro’s AI-driven camera system recently secured a 510(k) plus PCCP clearance, a regulatory pathway that explicitly allows for autonomy upgrades via software [Source: PR Newswire]. Simultaneously, ARPA-H’s AIR program is funding fully autonomous interventions, aiming for systems that can perform stroke thrombectomies without direct human input [Source: ARPA].

This healthcare shift mirrors the broader shift toward robotics and the "spatial intelligence" movement in AI. At the most fundamental level, the current traction around world models will enable robotics to function and scale in unprecedented ways. Industry heavyweights have long preached about and are now betting on this transition: Yann LeCun is leaving Meta to build world models that plan and act [Source: Observer]; Fei-Fei Li’s World Labs has raised ~$230M to teach models 3D reasoning [Source: Tech Funding News]. Surgery and interventional cardiology are simply the clinical instantiations of this trend. The AI doctor is beginning to make the shift from reasoning about care to executing it in the physical world.

1e. Asymmetric distribution: patient demand will drive AI doctor adoption

“AI doctors” at higher levels of autonomy will scale on the consumer side first, not because the technology is better there, but because the economics are. On the clinician side, AI is fighting an uphill battle. Take radiology: you're competing with specialists who already operate at 99%+ accuracy after a decade of training. As Graham Walker put it, "So if your AI is trying to AUGMENT a radiologist, going from 99% to 99.1% accuracy is extremely expensive for that incremental gain, and in fact that 1 in 1000 change now slows down your radiologist to see if the AI is right or not. If you’re trying to REPLACE radiologists then, fine — but now you’ve just shifted your costs from labor to liability. You’ll need malpractice coverage for your algorithm, and you're now also just shifting additional liability onto the non-radiologists ordering the tests as well." [Source: LinkedIn] Unless you're replacing the radiologist outright, the ROI doesn't pencil. Even then, significant questions remain around liability. Adoption has been slow for exactly this reason.

On the patient side, the comparison is fundementally different. You're not competing with radiologists. You're often competing with nothing, and otherwise are functioning as a low-cost, low effort adjunct or alternative to actually seeking care. For many people, the alternative to an AI doctor isn't a human doctor; it's doing nothing at all, Googling symptoms at 2 am, or waiting three weeks for a PCP appointment they'll probably cancel.

Thus, the same level of performance adds massive value. Distribution is also trivial: app stores, search bars, text boxes. No credentialing committees, no hospital IT approvals, no reimbursement codes. Just a question and an answer.

The clinician-facing tools that are working, such as OpenEvidence and ChatEHR, aren't really "AI doctors." They're reference tools that doctors pull in when they decide they need help. The locus of control stays with the physician. Clinicians are generally comfortable delegating cognition, synthesis, and recall, but far more resistant to ceding final decision ownership and liability. While their product roadmaps likely include shifts towards autonomous decisionmaking, today they are fundamentally different products from systems that make diagnoses autonomously.

The asymmetry is stark: on one side, highly trained specialists with unclear ROI and real liability risk. On the other hand, end users stampeding toward instant, cheap answers with no gatekeepers. As we’re already seeing, “AI doctors” will hit scale in consumer channels first.

Section takeaways

The “AI doctor” is not a product. It’s an inevitability born of unmet demand and learned trust.

The question is no longer if machines will practice medicine, but how society will define “practice.”

As with every technological shift, semantics trail behavior. As users take medical advice from Dr. ChatBot, the market is already writing the definition.

Section 2: Technology & Readiness

2a. Assessing Performance

As “AI doctors” scale, the benchmarking landscape for medical AI has steadily progressed from superficial metrics, such as board exam performance, towards practical metrics, such as clinical safety/harm, multi-step decision-making.

The majority of research to date has been about recall, focusing on “accuracy of question answering for medical examinations, without consideration of real patient care data.” [Source: JAMA] GPT-4 passing the USMLE at >90% accuracy was a headline, not a practical evaluation of efficacy. Multiple-choice boards prove encyclopedic memory. However, they say little about their ability to practically function as medical decision-makers: a much more convoluted and difficult process involving information gathering, multimodal investigation, building a differential diagnosis, and settling on a leading diagnosis and action plan.

More sophisticated “second-gen” benchmarks factor in this dynamic nature of true clinical decisionmaking:

OpenAI’s HealthBench: Released in May 2025, this evaluates the performance of models on 5,000 realistic conversations and grades them against 48,562 physician-written rubric criteria covering accuracy, relevance, and safety across emergencies, chronic care, global health, and more [Source: OpenAI]. Notably, the September 2024 models alone and model-assisted physicians outperformed physicians with no reference [Source: OpenAI].

Microsoft’s SDBench: Announced in June 2025, this feeds models 304 complex NEJM case reports that have been transformed into stepwise diagnostic encounters. It forces an agent (MAI-DxO) to behave like a clinician—asking questions and ordering tests under cost constraints. Paired with o3, MAI-DxO solved ~85.5% of cases (vs. 20% for unassisted physicians). A more cost-conscious configuration was able to achieve 79.9% accuracy with a nearly 20% cost reduction vs the unassisted doctors [Source: Microsoft].

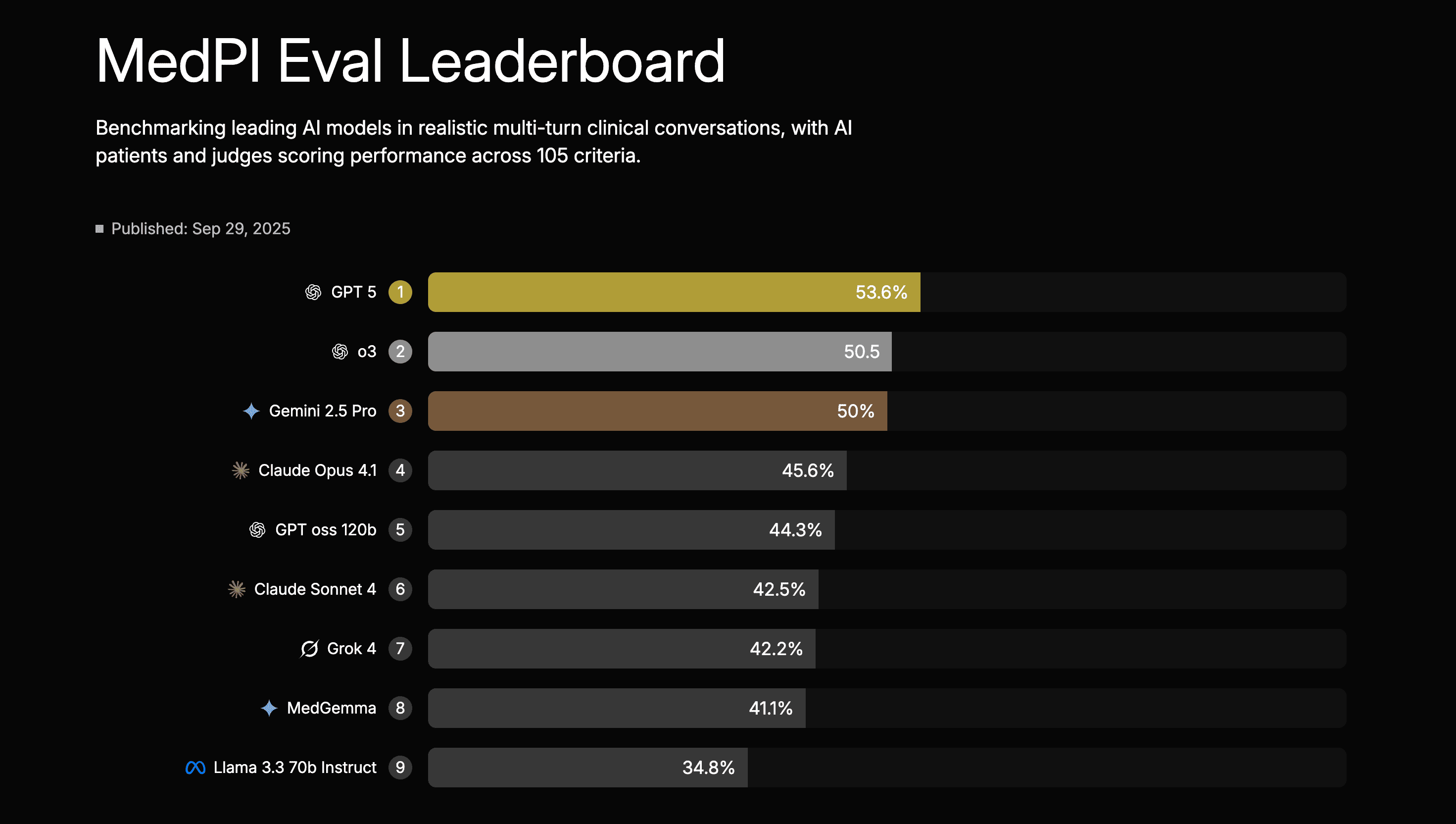

Lumos’s MedPI: Published in September 2025, this “interaction-first” benchmark runs 9 leading models through 7,010 simulated multi-turn doctor–patient conversations built from rich “patient packets” (longitudinal profiles with realistic histories and comorbidities) [Source: MedPI]. Each encounter is scored by AI “patients” and an LLM-as-judge protocol calibrated to human raters against 105 rubric criteria, grouped into 31 competencies and six high-level domains such as clinical reasoning & decision-making, patient safety & triage, communication, and professionalism. On the MedPI leaderboard, GPT-5 currently ranks first at 53.6% overall, with o3 at 50.5% and the next tier of frontier models (Gemini 2.5 Pro, Claude Opus 4.1, MedGemma, Grok 4, Llama 3.3 70B, etc.) clustered roughly in the 35–50% band, providing a granular, conversation-level view of model performance.

Cabral et al.'s R-IDEA: Published in 2023, this study from Massachusetts General Hospital and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center assessed GPT-4 against 21 attending physicians and 18 residents using 20 clinical cases, each with 4 sequential sections representing progressive clinical data acquisition. [Source: Cabral et al.] Participants generated problem representations and differential diagnoses scored via the R-IDEA framework—a validated 10-point scale evaluating clinical reasoning documentation across 4 core domains. GPT-4 achieved a median R-IDEA score of 10 (IQR 9-10) compared to 9 (6-10) for attendings and 8 (4-9) for residents, with the model demonstrating a 99% probability of high scores (8-10) versus 76% for attendings and 56% for residents (P = .002 and P < .001 respectively). While diagnostic accuracy and cannot-miss diagnosis inclusion were similar across groups, GPT-4 showed more frequent instances of incorrect clinical reasoning (13.8%) than residents (2.8%), highlighting the importance of multifaceted evaluation before clinical integration.

Most recently, NOHARM, short for “First, Do NO HARM,” developed by a Stanford and Harvard team, has emerged as the first truly high-powered benchmark centered on patient-level harm. If earlier generations focused on correctness (1st gen) and process-level reasoning (2nd gen), NOHARM represents the third generation, shifting the evaluative target to the question that matters most today: Not “How well does the model perform?” but “What are the risks if advice is followed?” [Source: Arxiv].

This reorientation is grounded in an observed reality: “This need [to understand patient safety] will only intensify as health systems move from human-in-the-loop to human-on-the-loop workflows… Continuous, case-by-case oversight is neither scalable nor cognitively sustainable.” [Source: Arxiv]

The benchmark uses 100 genuine primary-care → specialist referral cases across 10 specialties, each broken down into 4,249 concrete management actions (labs, imaging, medications, referrals, follow-up decisions). Every action is annotated by board-certified specialists using a WHO-style harm severity scale—bringing the focus to clinical consequences, not merely correctness.

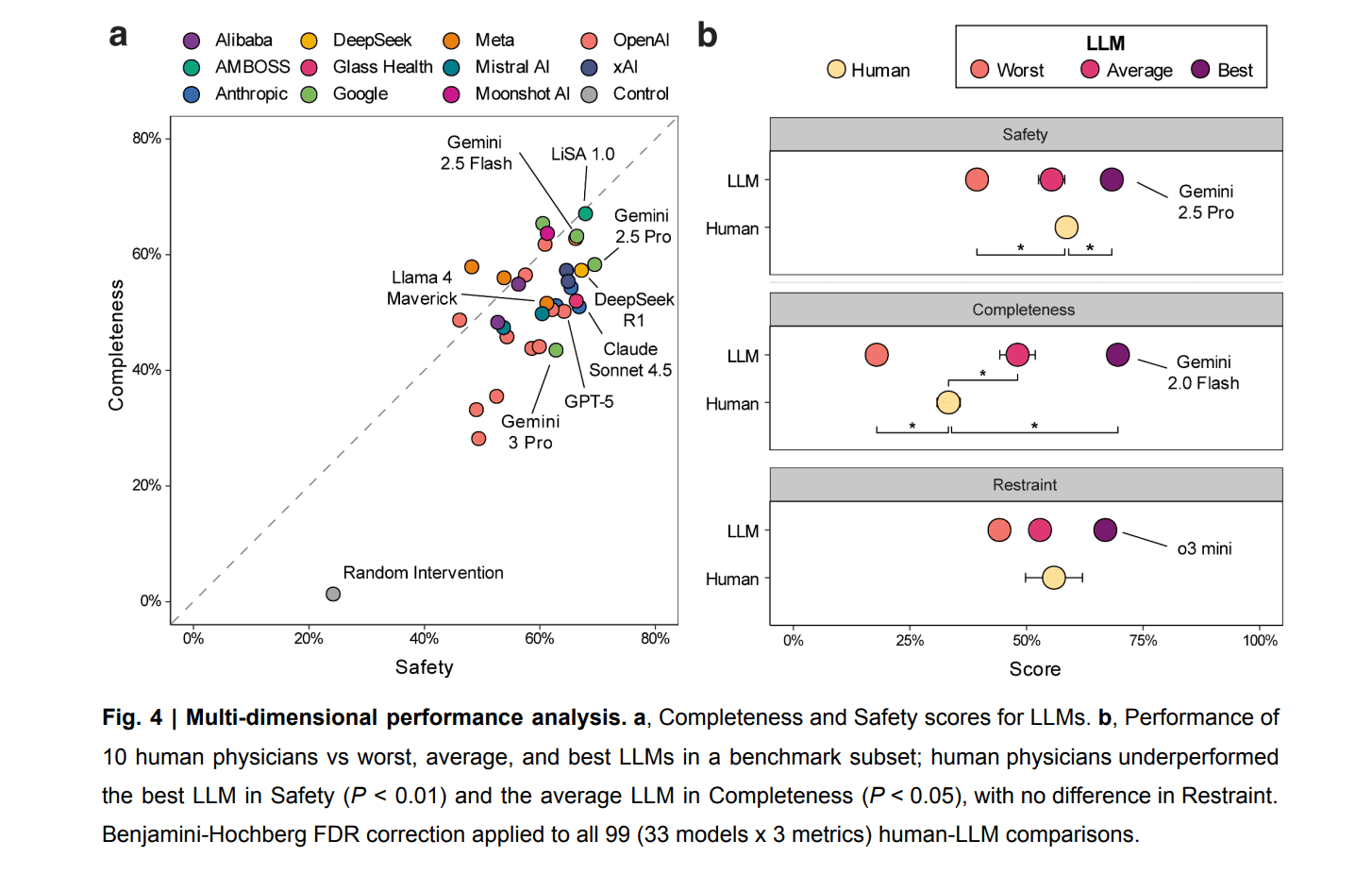

NOHARM puts hard numbers behind a question that is often hand-waved: how safe are AI clinicians, really? By explicitly measuring safety, completeness, and restraint across 31 LLMs, the benchmark reveals a clear but nuanced picture. Frontier models are not perfect. Severely harmful recommendations still occur in up to 22.2% of cases, driven largely by errors of omission (76.6%), underscoring that safety remains a challenging, unsolved dimension of clinical performance. But when evaluated head-to-head against humans under realistic conditions, the data consistently favors models. In a comparison with 10 board-certified internal medicine physicians using standard clinical resources, the strongest LLM outperformed physicians on safety (+9.7%, P < 0.001), and the average LLM exceeded physicians on completeness (+15.6%), while restraint was statistically indistinguishable between groups. Both humans and models are fallible, but across the dimensions NOHARM was designed to measure, leading models already match or exceed physicians on safety and completeness without sacrificing restraint.

The NOHARM leaderboard also reveals a critical anomaly. The top spot isn’t held by a household "frontier" model, but by AMBOSS LiSA 1.0. LiSA 1.0 is a specialized clinician-facing tool built on a curated medical knowledge base. Yet, almost no one outside of medicine, and surprisingly few within it, are even aware of AMBOSS’s model. The model doesn’t even crack the top 10 among AI tools physicians use, with generalized LLMs such as ChatGPT and Claude in the #2 and #4 spots, respectively. [Source: Offcall 2025 Physicians AI report] This validates a core thesis: beyond a certain threshold, model performance is moot without distribution.

NOHARM thus becomes the most deployment-relevant benchmark of this generation: a tool not only for assessing accuracy, but also for quantifying whether model behavior is clinically safe in a world where AI is already being used by patients for clinical decision-making. However, one important caveat is that NOHARM is not comparing AI to doctors in the run-of-the-mill clinic visit. All of its scenarios come from Stanford’s eConsult service, which are cases that have already been escalated to specialists because the primary clinician wasn’t fully confident in the next step. The benchmark is therefore deliberately weighted toward unusual, ambiguous, and high-stakes problems rather than everyday primary care. This design limits how broadly we can generalize the exact scores reported from this particular study.

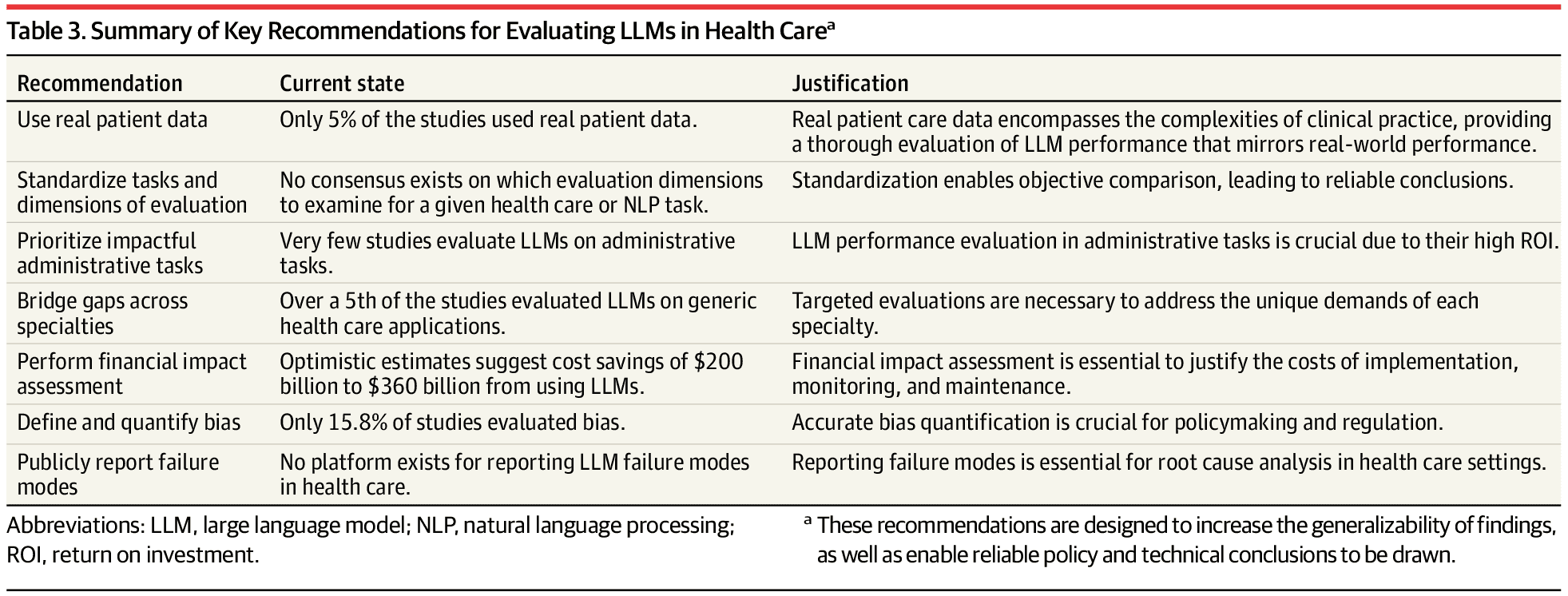

Before we declare victory on benchmarks, it’s worth being clear about what’s still missing. The table below, drawn from an October 2024 JAMA review, reflected the state of play at the time and remains highly relevant today. The next generation of AI doctor models will need to be evaluated on real patient data, using standardized task frameworks and specialty-specific benchmarks, not generic Q&A. They will need to demonstrate ROI in high-volume administrative and clinical workflows, explicitly quantify bias and failure modes, and support public, auditable reporting when things go wrong. [Source: JAMA]

As the "AI Doctor" matures, the goalposts are moving. We have graduated from the vanity metrics of chatbots passing the USMLE, to rigorous, validated simulations from top academic institutions. While each study has its limitations, taken together, these benchmarks point toward an emerging reality: for the cognitive doctoring part of medicine, there are scenarios where the AI doctor beats its human counterpart.

Where benchmarks go next

The benchmarks we have today measure AI performance when the clinical question is already framed and the data is clean. But real medicine often starts with ambiguity and competing priorities: a patient presenting with chest pain who's also anxious about three other symptoms, where the clinician must decide which thread to pull and which concerns can wait; a patient with multiple chronic conditions where new lab findings could represent benign variation or early decompensation; a teenager with abdominal pain where the exam findings don't match the story. The critical skill isn't just diagnostic reasoning but medical judgment: deciding what to focus on, what to ignore, and what to defer. Current benchmarks capture reasoning well but struggle with judgment. Current LLMs can't perform physical exams to triangulate findings the patient isn't reporting or use exam data to determine clinical priority. They struggle to redirect conversations appropriately and are trained to be agreeable rather than clinically firm. The data suggests AI is approaching human-level performance for straightforward cases, but clinical judgment in ambiguous encounters remains the proving ground. The winning benchmarks of the future won't just test what AI recommends but how it navigates competing priorities and acts when the right answer isn't clear.

2b. Leading models & results

The results from the 2024–2025 benchmarking wave are unambiguous. Although individual studies carry important caveats and additional data are needed, frontier models have not merely caught up to physicians in clinical reasoning and diagnostic decision-making; they have repeatedly demonstrated that they have statistically surpassed them.

When we aggregate the signal from high-powered assessments like NOHARM, SDBench, and HealthBench, a clear pattern emerges. In simulated environments where the necessary data is laid out and the variable is clinical "cognitive horsepower", the agent consistently beats the unassisted human.

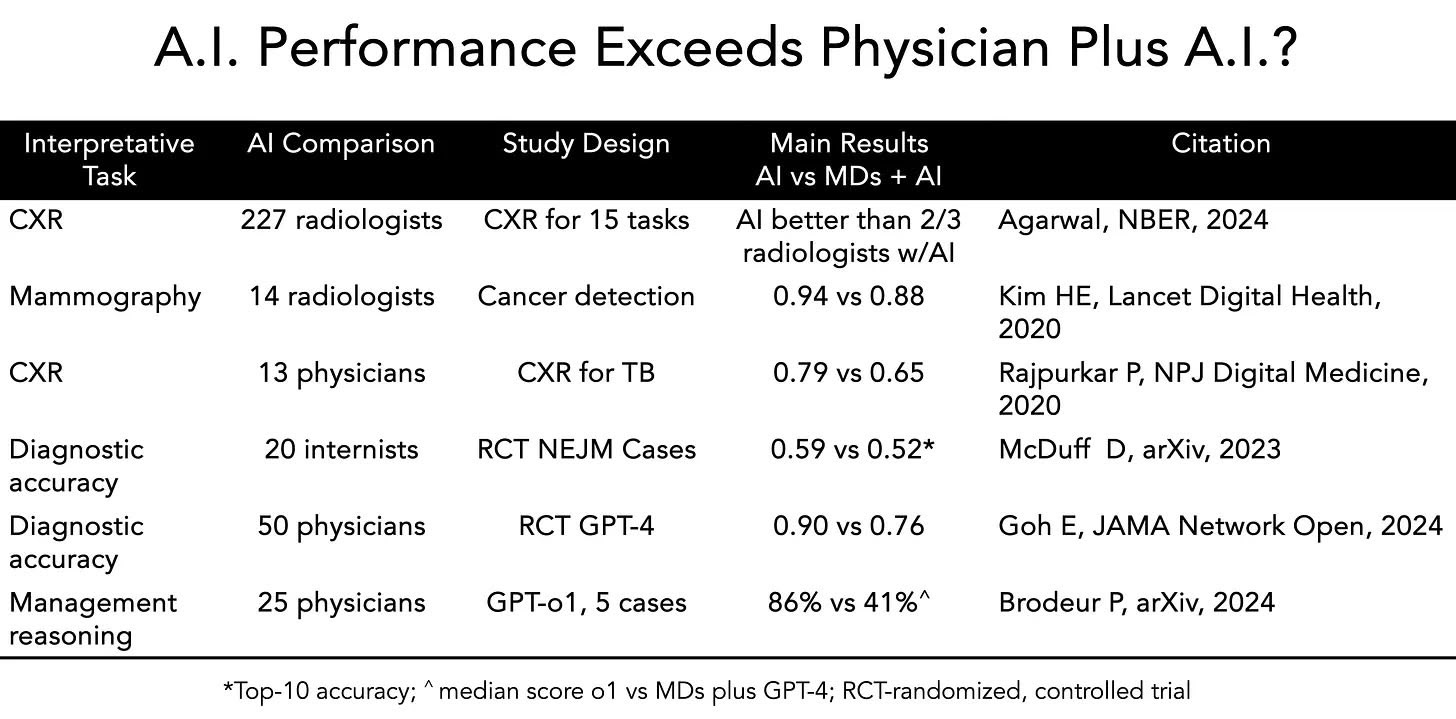

In addition to these benchmarks, a number of stand-alone academic studies also support this conclusion. Perhaps most striking is the body of work called out by Eric Topol earlier this year demonstrating that AI alone out-performs doctors with AI. [Source: Substack]

The skeptics' argument has always been: "Simulations aren't reality." These assessments are done on pre-determined, orchestrated cases where the data is relatively structured and the problems are meant to be solved. This is why the Doctronic study is the most critical investable signal of the year.

The "Doctronic" Signal: The End of the "Human in the Loop" Safety Blanket?

Unlike simulations, the Doctronic study compared a multi-agent AI against board-certified physicians in real-world urgent care encounters. The results dismantle the assumption that humans are the safety net. [Source: Doctronic]

Concordance: In 81% of cases, the AI and the human doctor agreed perfectly.

The "Superhuman" Delta: In the 19% of cases where they disagreed, an expert panel adjudicated who was right. The AI was correct four times more often than the human (36.1% vs 9.3%).

The Counterarguments: Why Most "AI Falls Short" Studies Miss the Mark

Not all recent data points in the same direction, and it's worth addressing the studies that appear to show humans retaining an edge. However, most of these studies suffer from a fatal flaw: they test yesterday's models.

Take the widely cited Takita et al. meta-analysis published in NPJ Digital Medicine in 2024, which analyzed 83 studies and concluded that AI models showed an overall diagnostic accuracy of just 52.1%, with no significant difference versus non-expert physicians but significantly worse performance than expert physicians (p = 0.007) [Source: NPJ Digital Medicine]. On the surface, this seems damning. But a closer look at the underlying data reveals the issue: the studies showing expert superiority overwhelmingly tested deprecated models like GPT-3.5 and Llama 2. When the analysis is restricted to frontier models—GPT-4o, Llama 3 70B, Gemini 1.5 Pro, Claude Sonnet, Claude Opus—the performance gap disappears. No significant difference versus expert physicians. The meta-analysis isn't wrong; it's just aggregating across model generations that are no longer clinically relevant.

Similarly, the Hager et al. framework, while methodologically rigorous in its use of 2,400 real MIMIC-III cases across four abdominal pathologies, tested Llama 2. While perhaps the best benchmark out at the time of publication, this model is now so dated it doesn't even appear on current benchmarks like NOHARM [Source: Hager et al.]. The framework itself remains valuable for future work, but the performance data no longer reflects the state of the art.

The One Area Where Humans May Still Hold an Edge: Reasoning Under Uncertainty

Returning to our earlier point that we lack good benchmarks for clinical judgment: we may be systematically undercapturing the one domain where humans still hold a meaningful edge—reasoning under uncertainty. A 2025 study using Script Concordance Testing (SCT), a decades-old clinical assessment tool that measures how new information adjusts diagnostic or therapeutic judgments, reveals a real potential gap [Source: NEJM AI]. SCT forces clinicians to update their beliefs dynamically as new data arrives, a core skill in real-world medicine.

The study tested 10 state-of-the-art LLMs against 1,070 medical students, 193 residents, and 300 attending physicians across 750 SCT questions spanning multiple specialties. OpenAI's o3 achieved the highest performance at 67.8%, followed by GPT-4o at 63.9%. Reasoning-optimized models like o1-preview (58.2%) and DeepSeek R1 (55.5%) performed lower, with Gemini 2.5 Pro at 52.1%. While models matched or exceeded student performance, they did not reach the level of senior residents or attending physicians.

More revealing than the raw scores was the response-pattern analysis: models showed systematic overconfidence, overusing extreme ratings (+2/−2) and seldom choosing neutral (0) responses. This suggests that chain-of-thought optimizations, which excel at deterministic reasoning, may actually hinder the kind of probabilistic, hedged thinking required under clinical uncertainty. This is not a model versioning problem. It's a fundamental challenge in how current architectures handle ambiguity.

The Bottom Line: Context Matters, But the Trend Is Clear

These findings don’t contradict the broader signal—they sharpen it. Frontier models have largely closed the gap on deterministic clinical reasoning, and the remaining work is extending those strengths into more nuanced uncertainty calibration rather than overcoming a fundamental limitation. Model generation matters enormously: conclusions drawn from 2023-era systems tell us little about 2025 capabilities. And simulated benchmarks, while useful, cannot substitute for real-world evaluation, which is precisely why the Doctronic study carries such disproportionate weight.

When we focus on the most recent, highest-powered assessments using frontier models such as NOHARM, SDBench, and HealthBench, the pattern is unmistakable. In a growing set of well-scoped environments where clinical cognitive horsepower can be isolated and measured, the latest AI models are not just competitive; they are, on average, outperforming unassisted physicians.

This flips the industry narrative. We traditionally view the AI as a "Co-pilot" that requires human oversight to prevent hallucinations. The data suggests the opposite may soon be true: the human is the source of variability and error, and the AI is the stabilizing force. The AI didn't hallucinate; it caught things the humans missed.

2c. “Good enough” care

While all of this benchmarking provides necessary proof points as the march towards autonomy continues, a key question for real-world deployment is: How good is “good enough”?

Spencer Dorn has a phrase I keep coming back to: “good enough” care [Source: Linkedin.com]. Not second-class care. Just care that beats the alternative many patients actually face, delayed access, fragmented one-off visits, or no care at all. The core deployment question isn’t whether an AI doctor matches academic physicians at the computer working through simulated scenarios; it’s whether it beats the care people actually get (or don’t get) today [Source: JAMA]. For large swaths of use cases, the comparator is not a top-decile clinician; it’s the fact that millions of patients are having trouble accessing any doctor at all. The threshold for adoption will differ based on the setting and the comparator. For patients struggling to access care through overburdened health systems, an AI that provides an easy to access, “good enough” answer could be a game-changer.

A recent Merritt Hawkins survey found that a middle-aged woman in Boston with pelvic pain waits an average of 84 days to see a gynecologist, and an older man in Boston with reflux waits ~60 days for a gastroenterologist [Source: Linkedin.com]. These are in one of the most doctor-dense cities in America; the waits can be far longer in rural areas or for Medicaid patients.

Not only are delays common, but even when you do get to the doctor, the encounter may be suboptimal. Primary care visits are short and follow-up can be haphazard. Many patients resort to walk-in clinics or telehealth startups that address one issue at a time, often with no continuity. It’s no wonder that direct-to-consumer services like Hims & Hers, Ro, and other telemedicine startups have thrived by trading the traditional doctor-patient relationship for quick, convenient access to “good enough” care for things like hair loss, erectile dysfunction, or birth control. Patients showed they’re willing to trade intimacy for immediacy. As Spencer Dorn, MD, put it, these companies proved that “good enough ‘care’” delivered with convenience will attract patients who are otherwise left waiting [Source: Linkedin.com]. An AI doctor is simply the next step in that progression. If an algorithm can address your problem tonight, you might prefer it over waiting three months for an appointment, even if the AI isn’t perfect.

There's a paradox brewing in patient expectations that makes the "good enough" threshold even more complex. On one hand, patients are demanding more than ever. Social media and wellness influencers have conditioned people to expect perfection while simultaneously undermining trust in mainstream medicine, often with financial incentives to sell supplements or alternative treatments. On the other hand, the system itself is forcing patients to lower their standards out of necessity. If you can't see your primary care doctor for six weeks and can't get a neurosurgery consult for three months, of course you're going to demand every test and intervention the one time you actually get in the door. Watchful waiting and anticipatory guidance feel like luxuries when the next appointment might be months away. And now, with healthcare costs escalating sharply, patients are increasingly asking what they're actually getting for their money. The Luigi Mangione case and its aftermath have brought cost and value conversations into mainstream discourse in ways that were previously confined to policy circles.

This creates a strange opening for AI doctors. Patients want perfection but can't access it. They're willing to settle for "good enough" because the alternative is often nothing, but they're simultaneously more skeptical and demanding than ever before. An AI system that delivers consistent, evidence-based care on-demand at low or no cost thread this needle in ways traditional care models cannot. It won't satisfy the perfection expectation, but it can meet the access, cost, and consistency expectations that matter more in practice.

There’s historical precedent for this notion of “good enough” scaled service. More than a decade ago, surgeon and author Atul Gawande wrote an influential essay called “Big Med”[Source: health.harvard.edu], drawing an analogy between medicine and the Cheesecake Factory restaurant chain. His argument was that American healthcare could benefit from standardization, checklists, and scale to deliver consistent quality at lower cost; much like a chain restaurant delivers reliable meals, as opposed to each chef (or doctor) reinventing the wheel for each customer. He observed that in medicine, “every clinician has his or her own way of doing things,” leading to huge variability in costs and outcomes. Gawande foresaw a shift “from a craft (small guilds of independent practitioners) to an industrial model (leveraging size and centralized protocols)”. AI in healthcare is arguably the ultimate realization of that vision: a way to encapsulate best practices and deploy them uniformly at scale. If an AI can recognize a rash with 90% accuracy, it will do so the same way every time, regardless of whether it’s 2 am or the doctor is having a bad day. That kind of consistency is both a promise and a challenge, because it can raise the floor on quality but also lower the ceiling if not carefully managed.

Importantly, “good enough” doesn’t mean settling for poor care; it means right-sizing the solution to the problem. Most cases of acid reflux (GERD), for example, do not need a gastroenterologist’s touch; they can be managed by primary care or even by a well-informed patient with over-the-counter meds. Yet in Boston, someone might wait 60 days for a GI consult for reflux. An AI could fill that gap easily: after ruling out alarm symptoms, it could initiate lifestyle advice or a trial of medication today, not two months from now. For the patient, that’s a tangible win. Dorn encapsulates this by saying his “purist” side recoils at lowering the bar, but the “pragmatist” side recognizes it’s necessary, with appropriate guardrails, to meet people where they are [Source: Spencer Dorn on Linkedin.com]. In practice, guardrails might include limiting AI to certain complaints, having a human clinician review a subset of cases, or programming the AI to escalate to a human if uncertainty or red flags are detected.

It’s worth noting that patients have already shown they will tolerate “Big Med” in exchange for access and convenience. We’re already seeing the “production line” approach in limited form: telehealth formularies for common conditions, algorithmic care pathways in retail clinics, etc. Companies like Hims and Ro showed that patients would accept a somewhat one-size-fits-all approach (online questionnaire + standard treatment) for convenience. The success of minute clinics, telemedicine apps, and online prescription services all point to a willingness to trade the traditional doctor-patient relationship for faster, easier service as long as the outcome is acceptable. AI-driven services will extend that model to far more conditions, gradually expanding the scope of “good enough” autonomous care.

For a large fraction of everyday healthcare needs, an AI that is “good enough” (say, performing at the level of a competent family medicine doctor) will find a willing market, especially if the alternative is no care or delayed care. If it’s significantly cheaper, more accessible, and continuously improving, it could actually raise the overall standard of care by catching issues earlier and managing chronic conditions more tightly.

In practice, the early wedges for AI doctors will be:

Low-acuity, high-volume conditions that overwhelm primary care

Stable chronic disease checks (BP, diabetes titration, refills)

Triage and routing (“Is this safe at home, or do you need ED/urgent care?”)

In each of these domains, the threshold is not perfection; it is clear, measurable superiority to what most patients get today, under tight guardrails. Benchmarks like HealthBench, SDBench, and NOHARM suggest the cognitive engine is already there.

It is also worth remembering that today’s models are the worst they will ever be. They are improving at a breakneck pace through both steady gains in performance and stepwise advances in model architecture. Stanford’s ChatEHR offers a concrete example. The system allows clinicians to query a patient’s entire medical record with exceptional accuracy. In a talk at Stanford, Nigam Shah noted that even the most diligent clinicians, including those who pre-read every chart, remain constrained by human limits: how many aspects of care they can review and how far back in time they can reasonably synthesize. ChatEHR, by contrast, operates over the full longitudinal record by default. While ChatEHR remains a provider-facing tool, the directional signal is clear. Context-rich, longitudinally aware AI materially improves clinical reasoning and workflow. A patient-facing analog with full record access, benchmark-validated reasoning, and unlimited time would represent a step-function improvement over systems that already outperform clinicians on core reasoning tasks.

Section takeaways

The benchmarking bar has shifted from superficial metrics like board-exam accuracy to rigorous evaluations of reasoning quality, interaction safety, workflow execution, and patient-level harm.

In those environments, top (and some specialized) models already match or beat physicians on cognitive performance in specific scenarios; each of the cited studies has caveats, but the overall trend is clear: the real bottleneck is reliable execution and integration rather than medical knowledge.

In the real world, the comparator is often delayed or absent care, not a top decile clinician. “Good enough,” domain-bounded AI doctors will scale fastest where access is worst and guardrails are clearest.

Section 3: Jevons’ Paradox in Healthcare AI

Jevons’ Paradox describes the phenomenon where efficiency gains lower the cost of access and, paradoxically, increase total consumption rather than reduce it. Our read of the early data suggests LLM front doors already add roughly 16 million U.S. visits per year (see table below), not subtract them, and that number will grow. In a system already facing a severe physician shortage, this further strains an already fragile supply base.

Hard data on whether LLM “front doors” deflect demand (reassure patients into self-care) or activate demand (pull more people into the system) is still thin. One of the few peer-reviewed snapshots is a 2024 JMIR cross-sectional survey of people using ChatGPT for online health information: 23.2% reported scheduling an appointment based on ChatGPT output, 15.3% reported canceling an appointment, and 35.6% reported requesting a test or referral (multi-select). Usage was frequent (40% using it 2–3x weekly or more), and about a quarter reported using it for 6 months or longer. All behaviors in the survey are reported cumulatively. Although roughly 75% of respondents reported using ChatGPT for health information for six months or less and only ~25% for longer than six months, we adopt a simplifying six-month attribution window to reflect the long-tail contribution of heavier, longer-tenured users [Source: JMIR]. In translating incidence into system-level volume, we also had to explicitly treat reported incidence as a proxy for frequency. To translate that into system load, we combine those conversion rates with KFF polling that 17% of U.S. adults use AI chatbots at least monthly for health information and advice [Source: KFF]. Even in this loose, non-integrated channel, the arithmetic from this single paper points to net visit creation, not net deflection, which is directionally consistent with older symptom-checker evidence suggesting triage tools tend to be risk-averse and push users toward care [Source: Europe PMC].

Illustrative translation of one ChatGPT user study into U.S. visit volume

Step

Input (source)

What we compute

Result

Source

1

U.S. population

N/A

340M

Source

Interpretation: Using the best available signal from a single survey of ChatGPT health-info users, the net effect is positive utilization (about +1.34M visits per month, or +16.1M per year across the U.S.), even before you add any embedded scheduling or referral rails. The exact magnitude is highly uncertain (self-reported, multi-select outcomes; unclear timing; heavy-user bias; incidence rather than frequency measurement) and more data is greatly needed, but the directional takeaway from this paper is straightforward: in a non-integrated channel, measured “activation” exceeds measured “deflection.”

In context, the U.S. healthcare system already delivers on the order of one billion visits annually, so this is not a system-breaking swing on its own. But it is directionally important. In a system constrained by physician supply, even a low-single-digit increase in demand is consequential in a system operating above capacity.

There is a critical nuance hiding inside the utilization math: we do not know the quality mix. LLMs might reduce some waste by helping patients self-triage, while increasing other waste by making escalation feel easier and more justified. Net visits can rise even if unnecessary visits fall, if necessary visits rise more. The only question that matters is whether the marginal visit is outcome-positive. Until we can tie “LLM advised escalation” to downstream outcomes and total cost of care, a higher conversion rate should be treated as a supply-side stress test, not as proof of better care.

It’s also interesting to consider what happens next. These signals are coming from ChatGPT, a loose, non-integrated channel with no native scheduling, no referral routing, and no economic incentive to convert a conversation into a clinical encounter. Even so, the data already show net visit creation. As these interactions migrate into vertically integrated AI front doors, the activation rate will not merely increase; it will structurally step-change upward. Their entire business model depends on converting triage into billable care, which means removing friction by design: identity is known, context is pulled, and escalation is one click away. If the AI ends the interaction with “this might be serious, tap here to see a doctor in 10 minutes,” a much larger share of users will convert by default. In other words, today’s activation rates are a floor, not a ceiling. As AI front doors absorb more of these conversations, Jevons’ paradox does not just persist; it accelerates.

The release valve - true autonomy

While escalation should absolutely have to earn its keep, with every “book now” tied to a measurable prediction and a measurable outcome, that is still a partial fix. In a supply-constrained system, there are only two durable equilibria: suppress demand through rationing, or expand supply through autonomy. True autonomy is the only path where access can scale without dragging clinician minutes along with it. Everything short of that is, by default, a demand amplifier unless it is deliberately engineered to substitute for visits via closed-loop self-care, asynchronous management, and outcome-linked escalation. The long-term winners will not just route demand better; they will collapse entire categories of care that no longer require a human in the loop.

Section 4: Is Society Ready?

4a. The trust paradox: self-driving cars vs. AI doctors

When we ask whether society is ready for AI doctors, it helps to look at the only other place where applied AI is already making life-and-death decisions at scale: the AI driver. Robotaxis are our closest real-world analog for high-stakes autonomy, and they expose a striking mismatch between actual safety and perceived safety.

On the road, the numbers are clear. Neurosurgeon and Scrub Capital founding partner Jon Slotkin did a deep-dive on Waymo’s driverless service as a telling case study. Waymo’s driverless service has logged nearly 100 million fully driverless miles with dramatic safety gains: peer-reviewed analyses show about a 91% reduction in serious-injury-or-worse crashes, an 80% reduction in any-injury crashes, and a 96% reduction in injury-causing intersection crashes versus human drivers on the same roads [Source: Slotkin Essay NYT]. In clinical terms, this looks like the kind of “overwhelming benefit” that would stop a randomized trial early, and yet public and political trust still lags far behind. Only 13% of U.S. drivers say they would trust riding in a self-driving vehicle, and a solid majority still report being afraid [Source: AAA Newsroom].

Healthcare is the mirror image. No fully autonomous “AI doctor” has FDA clearance for general diagnosis; we are still in the early innings of formal validation. But the demand side has already moved: recent surveys suggest that ~40% of Americans say they trust AI tools like ChatGPT for healthcare decisions, and over a third are using AI in some form to manage their health today [Source: Rolling Stones]. In other words, we have a domain (driving) where the evidence is superhuman but trust is scarce, and another (medicine) where trust is surging ahead of the clinical proof.

Robotaxis are a rough approximation of a control arm. They show that the readiness question for AI doctors is not primarily about statistics; it’s about the emotional, institutional, and experiential context in which those statistics land.

4b. Why people are ready for AI doctors

So why are people so willing to experiment with an AI doctor, while staying terrified of an AI driver, despite much stronger safety data on the latter? The asymmetry is not about math. It is about four forces that specifically favor AI in healthcare.

1) The visibility gap

Robotaxi failures are easy to see, even when they are minor. Most people know how driving is supposed to feel, so if the car hesitates at an unprotected turn, botches a lane change, fails to signal, brakes awkwardly, or blocks an intersection, the human in the seat notices immediately. Those errors are also public and photogenic, which makes them shareable and instantly attributable to “the AI system.”

Medical failures are often the opposite. Many of the mistakes patients worry about most live in nuance: a subtle missed red flag, the wrong framing of risk, a slightly off medication choice, the wrong follow-up plan. Most patients are not clinicians, so they cannot reliably detect when the reasoning is a little off, especially in the moment. That means AI errors in healthcare can blend into the already noisy background of delayed diagnoses, guideline deviations, and fragmented care. In transportation, the gap between “what should happen” and “what just happened” is visible in real time. In medicine, it often is not.

The result is asymmetric accountability. The robotaxi is judged against near-perfection because its failures are obvious and public. The AI doctor is judged against an already messy baseline because many failures are quiet, ambiguous, and hard for non-experts to audit.

2) Clinical ambiguity

Medicine is not deterministic. Even with guidelines, the decisions patients care about most often sit in gray zones: whether to operate now or watch and wait, how aggressively to titrate a drug, how to trade off side effects against benefit, how to interpret borderline findings.

Patients already experience this variability firsthand. Ask three reputable doctors and you may get three different plans. Second opinions frequently change diagnoses or treatment recommendations. The American Journal of Medicine reported that second opinions led to diagnostic changes in 14.8% and treatment changes in 37.4% of 6,791 patient-initiated cases [Source: AJM], while Mayo Clinic Proceedings found in a systematic review that 10-62% of second opinions yield major changes in diagnosis, treatment, or prognosis [Source: Mayo]. It’s also worth noting that clinicians often deliberately simplify or filter information to avoid overwhelming patients, manage uncertainty, and keep the encounter focused. LLMs invert that dynamic by giving patients access to the full information set and letting them explore nuance, alternatives, and edge cases on their own terms. In a domain where people already expect disagreement, an AI doctor can feel like an additional consultant to triangulate against rather than a single authoritative verdict. In driving, people expect the car to simply do the correct thing.

3) System mistrust

American distrust in the healthcare system has deep roots, grounded in real breaches of ethics and consent. The Tuskegee syphilis study, the nonconsensual harvesting of Henrietta Lacks’ cells, and decades of racial and economic inequity are not abstract history. They are part of the structural memory patients bring into the exam room. That memory is compounded by present-day friction: surprise billing, rushed visits, uneven access, and persistent outcome gaps. The result is a system that a large share of Americans no longer trust. Between April 2020 and January 2024, the share of U.S. adults expressing trust in physicians and hospitals fell from 71.5% to just 40.1% [Source: AJMC]. Gallup’s 2025 polling shows trust in doctors has dropped 14 percentage points since 2021, with ethics ratings now at their lowest level since the mid-1990s [Source: Gallup]. If you already feel dismissed or underserved by the human system, trying an AI doctor doesn’t feel like a leap. It feels like a substitution.

Transportation has a different baseline. People may worry at the margins, but they trust human-driven cars enough to use them constantly. Robotaxis are evaluated against an entrenched, familiar, mostly-working status quo. AI doctors are evaluated against a system a large fraction of consumers already experience as frustrating, inconsistent, or not fully on their side.

4) The judgment gap

Many clinicians work hard to be approachable, compassionate, and nonjudgmental. Plenty of patients feel deeply cared for, and good doctors invest real effort in making it safe to disclose anything. However, even in good relationships, it can still be easier to confess to a robot.

Healthcare is emotionally loaded. A large national survey published in JAMA Network Open found that between 61 and 81 percent of U.S. adults report withholding medically relevant information from clinicians, most often to avoid feeling judged, lectured, embarrassed, or blamed, despite many physicians’ genuine efforts to be approachable [Source: JAMA Network]. A chatbot interface lowers the social cost of honesty. You can admit substance use, financial constraints, or treatment nonadherence without watching a human reaction in real time.

AI doctors simulate compassion without fatigue and listen without judgment. That combination of endless patience plus anonymity earns a level of disclosure and deference most clinicians will never see in a 15-minute visit.

Put together, these four dynamics tilt trust toward AI doctors: (1) failures in medicine are harder for laypeople to see and attribute, while driving errors are immediately legible, (2) clinical decisions are already ambiguous and variable, (3) healthcare institutions are already on probation for many consumers, and (4) honesty is easier when you feel unjudged, especially when the interface is engineered to be agreeable. They do not imply safety or correctness, but they make experimentation feel psychologically easier in healthcare than in transportation. Robotaxis are the foil that makes this clear: in one domain, trust lags far behind safety; in the other, trust can race ahead of formal proof.

4c. Do we actually need the “human touch”?

The empathy question could easily have been folded into the prior section on why patients are so ready to trust medical AI. But the data on how people feel about AI vs. human bedside manner is striking enough that it deserves its own spotlight.

The intuitive story is that the last barrier to an AI doctor is the “human touch,” meaning the warmth, empathy, and rapport you get from a real clinician. The punchline from the last two years of data is almost the opposite. On multiple axes of perceived bedside manner, AI is already coming out ahead.

In a JAMA Internal Medicine study, clinicians compared real patient Q&As answered by physicians vs. ChatGPT. They preferred the chatbot’s answers 79% of the time and rated them as both higher quality and far more empathetic, with a roughly 10x increase in the share of responses labeled “empathetic or very empathetic.” [Source: JAMA Network]

A second line of work has moved into the electronic medical record. In a JAMA survey experiment, patients reading portal messages showed a mild but consistent preference for AI-drafted replies over clinician-written ones on helpfulness, completeness, and empathy until they were told a machine was involved, at which point satisfaction dipped slightly. [Source: JAMA Network] The content felt better, but the label “AI” made them uneasy.

The NEJM AI paper “People Overtrust AI-Generated Medical Advice Despite Low Accuracy” pushes this further. Participants evaluated responses where some AI answers were deliberately low-accuracy. They still rated those AI replies as more valid, trustworthy, and complete than physician answers, and reported a high willingness to follow the (sometimes harmful) AI advice, often at rates comparable to or higher than for the doctors [Source: OpenNotes]. An MIT-led summary put it bluntly: patients can’t reliably tell good AI medicine from bad, but they prefer the vibe either way [Source: Digital Health Insights].

This outcome is not especially surprising. Many consumer-facing LLMs are tuned to be highly agreeable because they are optimized for smooth, positive user experiences. The industry is actively grappling with “sycophancy,” where models over-validate, flatter, or align with the user even when they should push back [Source: Arxiv, Nature]. That behavior can be dangerous, because LLMs are often less willing to deliver uncomfortable guidance that clinicians routinely provide, such as confronting weight, smoking, or adherence because that confrontation risks disengagement. But the model is engineered to feel emotionally frictionless. There is no visible fatigue, no clipped tone, no subtle signal that you are taking too long or asking the wrong question. For patients accustomed to rushed visits or transactional care, that absence can register as empathy, even when it is really just alignment.

But there’s a catch that matters for real-world deployment. When responses are evaluated on content alone, AI often looks more empathetic. But when people are told a response came from an AI, they consistently rate it as less caring, less reliable, and less worthy of follow-through, even when the text is unchanged [Source: Nature, Nature]. The bottleneck is no longer generating empathy, but in whether patients are willing to accept empathy from a machine.

4d. Looking ahead

The AI doctor is not a bet on the future. It's a bet on formalizing what's already happening.

Patients have moved. One in six Americans asks chatbots for health advice regularly. They're uploading medical records to ChatGPT despite every warning label. They prefer AI empathy over human clinicians. The demand side has declared itself.

Evidence from a number of benchmarks and academic publications increasingly suggests that clinical reasoning in constrained, well-specified encounters is no longer the bottleneck; execution, context, and accountability are.

Below are what we see as four key structural gaps, and each one is a venture-scale opportunity:

1) Distribution as a clinical primitive

In healthcare, distribution is permissioned presence at the moment of need—an authenticated relationship, a default workflow, and a place the patient returns. That’s why patient portals and incumbent workflow surfaces matter as much as consumer growth loops. MyChart alone claims 190M+ patients, and Epic reports hundreds of millions of patient charts on the platform. [Source: Epic] Epic’s own research also underscores that portals aren’t passive “record viewers”; they shape real utilization (scheduling, messaging, adherence, no-shows), which is exactly the kind of closed-loop interaction surface a Stage 4 system needs to monitor outcomes and manage follow-up. [Source: mychart.org]

What this looks like in practice: the “front door” that wins is the one that can (a) capture the initial question, (b) identify the patient, (c) pull context, (d) route/act, and (e) close the loop. Counsel’s employer/payer-oriented positioning is one distribution path. [Source: PR Newswire] EHR/portal embedding is another. Consumer LLMs are the third. The likely winners will either own one of these chokepoints or partner into one while building defensible differentiation elsewhere.

2) EHR integration is not just “workflow.” It’s context completeness (and it’s required for Stage 4).

Stage 4 autonomy is structurally impossible without longitudinal context: meds, problems, allergies, labs, imaging, prior notes, prior failures, and system-specific constraints. That context lives in (and behind) the EHR, and interoperability initiatives like TEFCA are explicitly aimed at making cross-entity exchange more feasible at national scale—important, but still not the same as reliable, real-time, write-capable orchestration [Source: Becker's Hospital Review].

The key investor-grade bottleneck is that “reading the chart” is not enough. Autonomy requires deterministic execution inside messy, permissioned systems. Benchmarks like MedAgentBench show why this is hard: even strong medical agents can stumble on real EHR task execution, with overall success rates that are meaningfully below “clinical-grade reliability.” [Source: NEJM AI]. This is why EHR integration must be framed as both (i) the context layer that enables safer decision-making and (ii) the actuation layer that determines whether autonomy is even possible.

3) The clean data layer is both a training substrate and a real-time safety substrate.

EHR data is simultaneously (a) what everyone wants to train on and (b) the core real-time substrate for patient context. EHRs are not a clean record of clinical reasoning. They're shaped by billing codes, liability fears, and copy-paste templates, and ambient scribes may be adding even more slop into the mix [Source: NEJM]. Train AI directly on that substrate and you don't get better care; you get codified shortcuts and scaled mediocrity [Source: BMJ].

What's missing is a parallel layer: explicit, clinician-authored specifications of what "good" actually looks like across contexts. Not what got documented for reimbursement, but what clinicians actually meant. The real standards of care that experts intuit but the EHR flattens. Train naively on the raw clinical exhaust current EHRs contain and you risk scaling the documentation artifact, not the underlying clinical intent.

What this implies: the “clean data layer” is less about hoarding raw charts and more about creating an interpretable, clinician-aligned layer of specification: what “good” looks like, how uncertainty is represented, what constitutes harm, and what escalation thresholds should be. The NOHARM line of work is emblematic of this shift toward evaluating harmful actions and real clinical consequence rather than trivia-style correctness. [Source: arXiv]

4) Instrumentation turns text-only reasoning into examinable medicine.

True AI doctors can’t remain disembodied chatbots forever. As we move forward, we expect they will reliably ingest home vitals, images, wearables, point-of-care tests, and longitudinal signals, it closes the gap between “advice” and “care.” This is where the winners will look vertically integrated: distribution + context + actuation + sensors, with tight safety gating and auditability. (This layer is also where regulators will care most about measurable outcomes, because it creates observable clinical endpoints.)

The barriers of today

The four infrastructure layers above describe who will win. But there are prerequisite questions that determine whether anyone can win at all. These are systemic blockers that no individual company can solve alone and that prevent true autonomous AI doctors from existing at scale.